Clinical Resource: This Case Series Highlights The Clinical Effectiveness of The ActivHeal® WOUND CARE DRESSING RANGE

An educational supplement in association with

Clinical Resource

This Case Series Highlights The Clinical Effectiveness of The ActivHeal® WOUND CARE DRESSING RANGE

An educational supplement in association with

INTRODUCTION

Dr Karen Ousey, Reader in Advancing Clinical Practice, School of Human and Health Sciences, University of Huddersfield

The Department of Health (DH) (2009a; b; 2010a; b) has clearly identified the importance of maintaining and developing a quality service to all health and social care users. The QIPP agenda; Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention relates well to the specialities of tissue viability and wound care. Integral to maintaining and developing quality is the ethos ‘No decision about me without me’ promoted in Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS (DH, 2010a) that suggests patients should be involved in the decision-making process alongside practitioners. Indeed, patients will be in charge of making decisions about their care and will be able to choose which consultant-led team, general practitioner and treatment they have. The patients’ experience and satisfaction will be analysed through the use of Patient Reported Outcomes Measures (PROMs) and the amount of complaints received by healthcare users.

The importance of being able to ensure that care administered to patients is based on the best available evidence, and is cost effective has never been more significant, with the DH (2010a) identifying that the NHS must make efficiency savings of between £15-£20 billion by the end of 2013/14. In relation to tissue viability, Posnett and Franks (2008) had calculated that 200 000 people in the UK have a chronic wound with an estimated cost of treatment being £2.3–£3.1billion per year, these numbers will no doubt rise over the next few years as the ageing population increases.

The cost of preventing and treating pressure ulcers in a 600-bed acute trust has been estimated as being between £600 000 and £3 million a year (Touche, 1993). In 2010 the DH (2010b), estimated the cost of a category 3 pressure ulcer as being between £363 000 to £543 000 and a category 4 pressure ulcer as costing between £447 000 and £668 000. They identified that a reduction of 25% in pressure ulcers would mean 88 fewer pressure ulcers and a potential cost saving of £510 000 in health care per year, per NHS trust. Many pressure ulcers are preventable through risk assessment and the implementation of pressure-relieving measures with the DH promising that there would be ‘safer care for patients, who can be confident that they will be protected from avoidable harm’ (DH, 2009a:29). This can only happen if health professionals are provided with evidence that supports the use of wound dressings; education to develop their own knowledge and the skills to evaluate and understand the results of audit; reliability and validity of evidence and research presented to justify the use of wound care products.

ActivHeal® Alginate

ActivHeal® Aquafiber

ActivHeal® Foam Adhesive

ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid

Horkan et al (2009) explored whether or not systematic reviews, undertaken during the period 1998-2008, focusing on the issue of standard advanced wound dressings, added to the body of knowledge in wound dressings. They identified 13 systematic reviews and meta-analysis studies concluding that ‘it appears that consistent evidence that any one moist wound healing dressing is better than another in terms of wound healing is still lacking’ (Horkan et al, 2009: 304). Nelson and Bradley’s (2007) review of the Cochrane database exploring dressings and topical agents for arterial leg ulcers, identified that there was no evidence to allow any recommendations to be made on the choice of dressing type or topical agent.

A 3-month ‘in-use’ trial of the ActivHeal® dressings was undertaken by Lewis (2009) to ascertain the amount of money that could be saved if the Trusts’ current choice of wound dressings were replaced by those from the ActivHeal® range. ActivHeal® dressings were evaluated on care of older people, surgical, orthopaedic and neurology wards replacing the current foam, alginate, gel and hydrocolloid dressings on the chosen wards. At each dressing change, the nurse was required to fill out an evaluation form, at the end of one calendar month the completed evaluation forms were collected and each product was given an evaluation result as being either ‘worse than’, ‘equivalent to’, or ‘better than’ the previously used dressing. In terms of dressing performance, there was no obvious difference between the original ‘branded’ dressings and the replacement ActivHeal® range. The ActivHeal® dressings were rated as ‘equivalent to’ or ‘better than’ original dressings in almost all cases. The nursing staff registered no complaints about the change to the ActivHeal® range of dressings.

Following completion of the trial Lewis estimated that the annual cost saving on foam dressings alone was in excess of £41 000. The annual spend on wound dressings, prior to using ActivHeal®, was £103 029, the equivalent of 3 month spend, when using ActivHeal® range was £11 952 which equated to an annual spend of £47 808. Lewis acknowledges that this trial was only run over a limited period of time and therefore the findings may not be as accurate as a longer trial.

This supplement presents a series of case studies using the ActivHeal® range of products; foam non-adhesive; foam adhesive; alginate; aquafiber; hydrocolloid and hydrogel dressings. The methodology and patient sample will be expanded in the methodology section. The case studies highlight and discuss the use of the product range and the results that were experienced by the practitioners and patients. A variety of wounds were used to evaluate the product range with results showing that the products worked effectively; were cost effective; comfortable to the patient; easy to use and caused little discomfort on removal.

In the current health economic climate, cost savings are essential for each health professional and commissioner, without reducing the quality of care offered to each patient. The case studies presented in this booklet discuss, highlight and present a range of dressings that can provide a cost-effective dressing range that are evaluated by practitioners and patients positively.

AIM OF THE EVALUATION

The overall aim of the series of case studies is to provide clinical information on the usability, acceptability and clinical performance of the ActivHeal® range of products, when used in the management of chronic wounds of various aetiologies.

It is the aim of this series of evaluations to show progression of healing in all cases, irrespective of the healing variables and the setting of care.

METHODOLOGY SUMMARY

The evaluation reviewed the use of the ActivHeal® dressings in up to 11 patients per product section. Patients were recruited for the evaluation from the adult (>18 years) population who were routinely seen by the evaluating clinicians. The results were based on subjective data collected by the clinicians who took part in the evaluation.

Patients were included on the basis of having a wound that was suited to the product in accordance with the indications and contraindications in the ‘ instruction for use’ leaflet for each product. The decision to treat the patient with the ActivHeal® dressing was made before the patient was considered for inclusion in the evaluation and following a full wound assessment. The patients’ care was not affected and the wound dressing chosen was the most suitable following the patients’ assessment. The Trust’s standard practice of patient assessment and treatment was followed throughout the evaluation. Each dressing was applied and changed following a wound assessment by the registered practitioner and as required by the patient’s need or as dictated by the level of exudate, maintaining good wound care practice according to the Trust’s standard of practice. The ActivHeal® dressing was used as a primary or secondary dressing to suit the wound variables and in accordance with Trust policy. Table 1 provides guidance on which ActivHeal® dressings are appropriate for each wound type.

Consent was given by patients before inclusion within the evaluation. Consent was also gained to have photographs taken and published.

No further ethical approval was required as the use of the product was classed as an evaluation.

The assessment of the ActivHeal® products were conducted in the form of a series of evaluations that included dressing changes. The evaluations were completed by the relevant tissue viability nurse who attended the patient at each dressing change. During each dressing change the tissue viability nurse consulted with the attending nurse and patient regarding the progression of the wound; amount of exudate, level of pain experienced during dressing change and the ease of use of each dressing. The assessment of the wound was documented using data collection and evaluation forms provided by Advanced Medical Solutions Ltd. This enabled the data gathered to be collated to provide clinical evidence relating to the use and performance of the ActivHeal® dressing range in clinical practice; progression of the wound and the achievement of patient outcomes. The patient was also asked to give their opinion on how the dressing felt throughout its wear time and if it caused any discomfort on removal. Their comments were noted throughout the data collection.

The evaluation parameters/considerations that were applied are:

| Ability to manage exudate | Conformability | Maintaining moist wound environment |

| Ease of use | Overall rating | Assessment of wound bed/wound progression |

When the wound was reassessed the signs of infection had abated however the wound bed remained sloughy. As the wound bed was dry and contained 100% slough it was decided to use Activheal® Hydrogel as a primary dressing with Activheal® Hydrocolloid as a secondary dressing. Both dressings were selected to create a moist wound environment to allow the wound to autolytically debride. Hydrogels have the ability to hydrate a dry wound surface rapidly (Weir,2012) and debridement removes the non viable tissue to provide a wound environment that is less likely to support a heavy growth of bacteria (Vowden & Vowden, 2011). Hydrocolloids provide and maintain a moist wound environment that supports the healing process (Finnie, 2002) and that it also has the ability to facilitate autolytic debridement (Hegder, 2012).

The wound was redressed at 2-3 day intervals over a 2 week period and wound progress was documented.

Table 1: Appropriate dressing selection when considering ActivHeal® wound care range

| Wound type | Clinical considerations | Expected outcomes | Product category (primary dressing) | ActivHeal® product | Case study page reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necrotic | If clinically relevant, removal of necrotic tissue – barrier to healing | Clean, viable wound bed free of necrotic tissue | Hydrogel | ActivHeal® Hydrogel | 14 |

| Sloughy | Removal of sloughy tissue – barrier to healing | Clean, viable wound bed free of sloughy tissue | Hydrocolloid, Alginate, Aquafiber | ActivHeal® Alginate, ActivHeal® Aquafiber, ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid | 7, 8, 12 |

| Highly exuding | Manage excess exudate. Identify cause of excess exudate. Exudate could macerate peri-wound area | Reduction in exudate volume | Foam, Alginate, Aquafiber | ActivHeal® Alginate, ActivHeal® Aquafiber ActivHeal® Foam | 7, 8, 10 |

| Granulating | Protect the fragile granulating tissue. Stimulate growth | Healthy looking granulating tissue. Epithelialising wound | Foam | ActivHeal® Foam | 10 |

| Epithelialising | Maintain and protect epithelial tissue | Healed wound | Hydrocolloid | ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid | 12 |

ACTIVHEAL® ALGINATE RESULTSVisit product page

Corrine Edwards, Tissue Viability Nurse and Jodie Jordan, Tissue Viability Nurse, The Royal Wolverhampton Hospitals NHS Trust

The results gained from the dressing assessment of the ActivHeal® Alginate dressing range were collated and analysed.

Seven patient’s wounds were evaluated with the following wound types:

| Dehisced post-C-section surgical wound | Pilonidal sinus | Fungating breast wound |

| Leg ulcer x2 | Post-operative right above-knee amputation | Pressure ulcer category 4 right hip |

Patient progress was monitored and photos and assessments were taken at each dressing change to illustrate how the wounds had progressed using the ActivHeal® Alginate.

The seven patients comprised of four males and three females, the exudate levels of the wounds were assessed to be between medium and very high across the seven patients. On average the dressings were changed every 1-3 days dependent on the exudate levels. In all seven cases the ActivHeal® Alginate was used as a primary dressing and the secondary dressing was mainly the ActivHeal® Foam dressing. The data was analysed and is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Data from the ActivHeal® Alginate study

The evaluation of the data showed that in the case of ActivHeal® Alginate’s ability to manage exudate; 85% of the respondents were very satisfied, 26% satisfied and none dissatisfied. The staff reported that the ActivHeal® Alginate managed the exudate well.

In maintaining a moist environment 80% were very satisfied, 15% satisfied and none dissatisfied. Alginate fibres allow exudate to be absorbed into the dressing to form a cohesive gel, this ensures that the wound stays moist to provide an ideal wound healing environment (Winter, 1962). With regards to conformability of ActivHeal® Alginate, 81% were very satisfied and 19% satisfied. The dressing was also assessed for ease of use; 86% were very satisfied and 14% satisfied. It was also documented on the assessment forms that ActivHeal® Alginate was both easy to apply and remove and did not cause any underlying trauma to the surrounding skin of the wound. The staff also reported that the dressing did not break up on removal unlike some other alginates that they had used previously.

The ActivHeal® Alginate is a soft, conformable, absorbent dressing. In contact with wound exudate, ActivHeal® Alginate converts to a soft gel that provides an ideal moist wound environment that supports the wound healing process and aids autolysis (Beldon, 2010). It is indicated for moderately to heavily exuding wounds and to control minor bleeding in superficial wounds. It was reported that in the case of the fungating breast wound bleeding was controlled through the use of the ActivHeal® Alginate. Alginate fibres are a natural haemostat and therefore can be used to control minor bleeding (Thomas, 2000).

Anecdotally, the patients also reported that the dressings were comfortable when in place and were removed with ease and without discomfort. The high wet strength of the ActivHeal® Alginate ensures the dressing remains integral on removal.

Overall, 85% of the respondents were very satisfied and 15% satisfied with the product. This suggests that patients with wounds of varying exudate levels will have a positive experience when ActivHeal® Alginate is used. All of the wounds assessed and evaluated progressed through the healing continuum (Gray et al, 2006), reducing in size and displaying a reduction in levels of devitalised tissue.

ACTIVHEAL AQUAFIBER® RESULTSVisit product page

Carolynne Sinclair, Tissue Viability Nurse, Countess of Chester NHS Foundation Trust, Chester

The results gained from the dressing assessment of the ActivHeal Aquafiber® dressing range were collated and analysed.

Ten patient’s wounds were evaluated with the following wound types:

| Dehisced post-laporatomy surgical wound | Leg ulcers x3 | Pressure ulcer category 4 sacrum x3 |

| Cellulitis | Pressure ulcer caused by bandage damage | Pressure ulcer category 4 buttock |

Patient progress was monitored and photos and assessments were taken at each dressing change to illustrate how the wounds had progressed using the ActivHeal Aquafiber®.

The ten patients comprised of three males and seven females, the exudate levels of the wounds were assessed to be between medium and very high across the ten patients. On average the dressings were changed every 1-3 days dependent on the exudate levels. In all ten cases the ActivHeal Aquafiber® was used as a primary dressings and the secondary dressing was mainly the ActivHeal® Foam dressing. The data was analysed and is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Data from the ActivHeal Aquafiber® assessment

The evaluation of the data showed that in the case of ActivHeal Aquafiber®’s ability to manage exudate; 74% of the responses were very satisfied, 26% satisfied and none dissatisfied.

In maintaining a moist environment 80% were very satisfied, 20% satisfied and no dissatisfied. In regards to ActivHeal®Aquafiber’s conformability, 80% were very satisfied and 20% satisfied. The product was also assessed for ease of use; 83% were very satisfied and 17% satisfied. It was also documented on the assessment forms that ActivHeal Aquafiber® was both easy to apply and remove and did not cause any underlying trauma to either the surrounding skin of the wound or through maceration to the peri-wound area, a result of the reduced lateral wicking capability of ActivHeal Aquafiber®.

Anecdotally, the patients also reported that the dressings were comfortable when in place and were removed with ease and without discomfort.

Overall, 80% of the respondents were very satisfied and 20% satisfied with the product. This suggests that patients with wounds of varying exudate levels will have a positive experience when ActivHeal Aquafiber® is used. In all of the wounds assessed and evaluated the wounds progressed through the healing continuum (Gray et al, 2006), with all of the ten wounds reducing in size and level of devitalised tissue. One of the wounds progressed through the wound healing continuum despite having not shown any signs of healing for over a year.

CASE STUDY

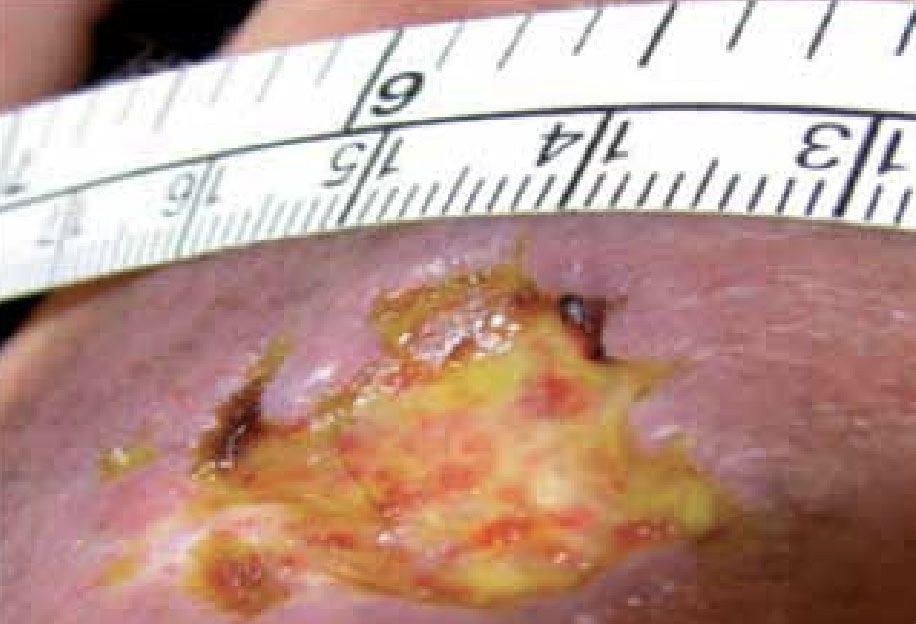

Mr T was an 87-year-old male with a history of angina. The patient was admitted with bilateral leg ulcers which had been present for 5 years (Figure 3). He was admitted as an emergency for a possible angioplasty and a possible amputation. The patient was also on nicorandil for his angina.

INITIAL PRESENTATION

At the initial examination the wound presented as an area of thick adherent slough with a high amount of exudate. The wound was very malodorous and painful for Mr T. He was referred to the tissue viability nurse who, on initial assessment, felt that some of the complications, including an anal ulceration, may be because of his medication (nicorandil) (McKenna et al, 2007). Nicorandil is a vasodilatory drug used to treat angina. It is used to maintain blood flow to the heart and prevent angina pain. Some of the side effects noted for this drug are skin and mucosal ulcers. There has also been research that has reported ulceration at sites including lower anterior leg ulcer (McKenna et al, 2007). Therefore, with the initial assessment, the patient’s medication was also changed and he commenced on reducing nicorandil.

Figure 3. Mr T’s leg at presentation

Figure 4. Mr T’s leg following two days of treatment

Figure 5. Four days after the application of ActivHeal Aquafiber®

Figure 6. Five days after the application of ActivHeal Aquafiber®

The wound was initially sharp debrided to remove any loose debris.

The priority for this wound was the continued removal of devitalised tissue through the facilitation of autolytic debridement, and the management of exudate while maintaining a moist wound environment. ActivHeal Aquafiber® was chosen to assist in the facilitation of autolysis of the devitalised tissue and manage the

exudate levels. The ActivHeal Aquafiber® is a soft, conformable, highly absorbent dressing. In contact with wound exudate ActivHeal Aquafiber® converts to a soft, clear gel providing an ideal moist wound environment that supports the wound healing process. It is indicated for moderately to heavily exuding wounds and to control minor bleeding in superficial wounds (Hawkins, 2010).

The secondary dressing that was used was ActivHeal® Non Adhesive Foam which was chosen to assist in managing the high levels of exudate and maintaining a moist wound environment. The ‘top film’ of ActivHeal® Non Adhesive Foam also provided a bacterial barrier to assist in the prevention of infection and contamination. The dressings were further secured using wool and crepe from toe to knee. Mr T was also commenced on intravenous antibiotics as he was diagnosed with a group A streptococcal infection.

Dressing changes took place daily; Figure 4 shows the wound following two days of treatment. The wound had started to debride autolytically with the application of the ActivHeal Aquafiber® and ActivHeal® Foam dressings. The wound had areas of granulation and ActivHeal Aquafiber® had managed the exudate successfully as there was no peri-wound maceration. The wound was reassessed and ActivHeal Aquafiber® was continued.

The wound continued to progress through the healing continuum, and at all times the peri-wound area remained intact with no signs of maceration (Figure 5).

A further 5 days later following daily applications of ActivHeal Aquafiber® the wound continued to improve (Figure 6). All slough had been removed and the wound was fully granulating. The peri-wound remained intact and there were no signs of maceration. There was also evidence of new epithelising tissue. At this point the patient also went for an angioplasty. A few days later the patient was discharged home.

The main challenge with this wound was to effectively remove the sloughy tissue and maintain a moist wound healing environment while also managing the wound exudate. Both the ActivHeal Aquafiber® and ActivHeal® Foam enabled the wound to progress through the wound healing continuum (Gray et al, 2006), following initial sharp debridement. The products demonstrated good clinical outcomes while allowing easy dressing removal without causing pain and trauma to the patient on removal. It should also be noted that the removal of nicorandil from Mr T’s medication appeared to be an aetiological factor of the leg ulcers which improved following its discontinuation. This would have assisted in the wound’s improvement along with administration of intravenous antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

The performance of ActivHeal Aquafiber® demonstrated by the results and the case study are encouraging. The evaluation showed that the ActivHeal Aquafiber® is an effective wound care choice that has shown good management of exudate and created the right environment for healing and wound progression. This is demonstrated by the fact that all the patients within the study showed signs of healing and wound progression. Eighty percent of respondents were very satisfied and 20% satisfied with the overall performance of the dressing.

The outcome of the study suggests that patients with chronic wounds will have a positive experience when ActivHeal Aquafiber® is used. This is because it has the required attributes of an absorbent fibre dressing for use on a range of chronic wounds.

ACTIVHEAL® FOAM RESULTSVisit product page

Elizabeth, Tissue Viability Nurse, East Lancashire NHS Trust

The results gained from the dressing assessment of the ActivHeal® Foam dressing range were collated and analysed.

Eleven patients’ wounds were evaluated with the following wound types:

| Pre-tibial laceration x5 | Evacuated haematoma | Dehisced post-surgical wound to ankle |

| Bitumen burn to foot | Pressure ulcer to medial aspect of ankles | Pressure ulcer to sacrum |

| Dehisced post-cardiac surgical wound |

Patient progress was monitored and photos and assessments were taken at each dressing change to illustrate how the wounds had progressed using the ActivHeal® Foam.

The 11 patients comprised of six males and five females, the exudate levels of the wounds were assessed between low to medium levels of exudate. On average the dressings were changed every 3-4 days. In all 11 cases the ActivHeal® Foam was used as a primary dressing. The case study presents a male admitted with a dog bite wound that was initially treated with a hydrogel and foam. However, on week two the hydrogel was discontinued and the ActivHeal® foam dressing used as a primary dressing and was not included in the initial evaluations. The data was analysed and is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Data from the ActivHeal® Foam assessment

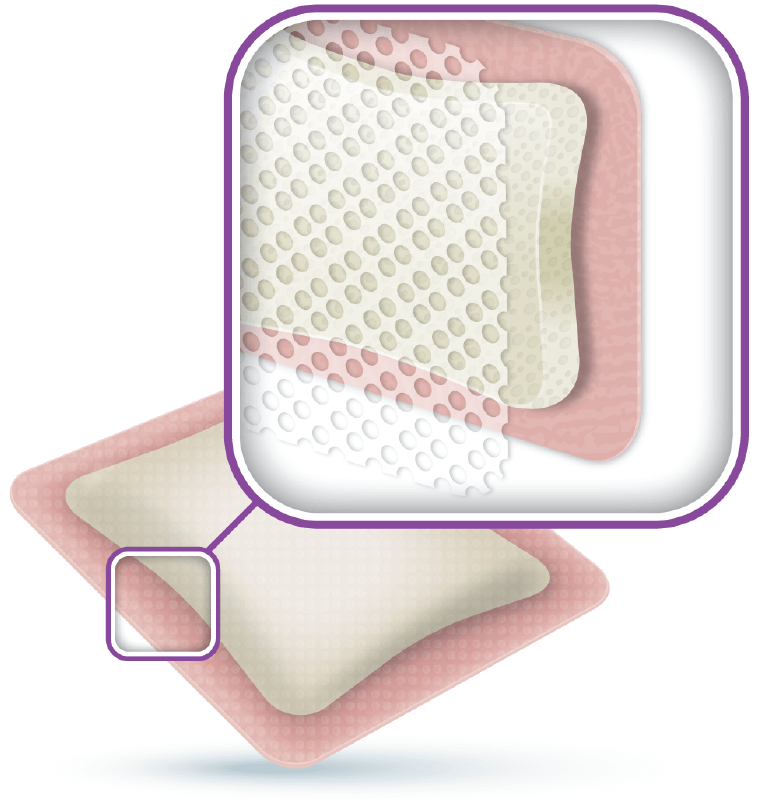

The evaluation of the data showed that in the case of ActivHeal® Foam’s ability to manage exudate, 90% of the respondents were very satisfied, 8% satisfied and only 2% dissatisfied.

In maintaining a moist environment 93% were very satisfied, 5% satisfied and only 2% dissatisfied. It was documented that one patient (representing the 2% dissatisfied) noted their skin had become slightly macerated owing to a sudden increase in exudate leading to an increase in dressing changes until exudate levels subsided.

When asked about ActivHeal® Foam’s conformability, 71% were very satisfied and 29% satisfied. The product was also assessed for ease of use where 98% were very satisfied and 2% dissatisfied.

Documentation on the assessment forms identified that ActivHeal® Foam was both easy to apply and to remove and did not cause any underlying trauma to either the surrounding skin of the wound or through maceration to the peri-wound area. One patient noted that the dressing had become dislodged, however, the patient had applied Epaderm ointment to dry skin prior to the use of the dressing, which may have caused the dressing to become dislodged.

Anecdotally, the patients also reported that the dressings were comfortable when in place and were removed with ease and without discomfort.

An overall rating of 93% of the respondents were very satisfied and 7% satisfied with the product, this suggests that patients with a range of wounds of varying exudate levels will have a positive experience when ActivHeal® Foam is used. All of the wounds progressed through the healing continuum (Gray et al, 2006), with a number of wounds reducing in size and level of devitalised tissue, and one of the wounds completely healed.

CASE STUDY: USING ACTIVHEAL® FOAM TO MANAGE EXUDATE AS A SECONDARY DRESSING

Mr P was a 56-year-old male with a history of a previous deep vein thrombosis and a non-insulin-dependent diabetic of 4 years. The patient had presented to Accident and Emergency with chest pain. On admission it was noted that the patient had a wound to his right thigh. The cause of the wound was a dog bite 4 months previously that he was self-treating with an antiseptic cream and dry dressing (Figure 8).

INITIAL PRESENTATION

Figure 8. Mr P’s wound at presentation

Figure 9. Wound on discharge, 3 weeks following initial assessment

At the initial examination the wound presented as an area of adherent slough with little exudate. The peri-wound area seemed fragile with some oedema. There was also evidence of some healed tissue. The priority for this wound was to debride the devitalised tissue through rehydration and the facilitation of autolytic debridement. ActivHeal® Hydrogel was chosen to assist in the rehydration of the wound, to remove the devitalised tissue and facilitate autolysis. The secondary dressing that was used was ActivHeal® Foam Adhesive which was chosen to ensure the hydrogel remained in place, while maintaining a moist wound environment. The ActivHeal® Foam Adhesive also provided a bacterial barrier to prevent infection and contamination but also enabled the patient to wash and shower as the dressing is waterproof. The ActivHeal® Foam has a range of features which ensure that excess exudate is absorbed away from the wound bed, and a moist healing environment maintained to create a wound healing environment.

Dressing changes took place every 2-3 days. The wound continued to debride autolytically with the application of the ActivHeal® Hydrogel and ActivHeal® Foam Adhesive dressings. Following a week of this dressing regime, which accounted for two dressings changes, the ActivHeal® Hydrogel was discontinued as all of the devitalised tissue had been removed and the exudate levels had increased. At this point the wound was reassessed and ActivHeal® Foam Adhesive was chosen to effectively absorb and retain the exudate, maintain a moist environment, facilitate moist wound healing and prevent contamination.

The wound continued to progress through the healing continuum, and at all times the peri-wound area remained intact with no signs of maceration which demonstrated that the ActivHeal® Foam Adhesive was managing the levels of exudate well. The patient was discharged home to the care of the district nurses (Figure 9).

To conclude, the main challenge was to effectively rehydrate the sloughy tissue and maintain a moist wound healing environment. Both the ActivHeal® Hydrogel, ActivHeal® Foam Adhesive along with ActivHeal® Foam Non Adhesive allowed the wound to progress. The products demonstrated good clinical outcomes while allowing easy dressing usage without causing pain and trauma to the patient on removal.

DISCUSSION

The performance of ActivHeal® Foam demonstrated by the results and the case study are encouraging. The evaluation showed that the ActivHeal® Foam has demonstrated effective management of exudate and created the right environment for healing and wound progression. Ninety-three percent of respondents were very satisfied with the overall performance of the dressing.

The outcome of the study suggests that ActivHeal® Foam can be used on a range of chronic wounds. Chronic wounds are defined by Collier (2002) as: ‘wounds that are failing to heal as anticipated or that have become fixed at any one phase of wound healing’.

ACTIVHEAL® HYDROCOLLOID RESULTSVisit product page

Margaret Caddy, Day Hospital Co-ordinator, Wound Clinic, Wallingford Community Hospital, Oxfordshire PC

The results gained from the dressing assessment of the ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid dressing range were collated and analysed.

Ten patient’s wounds were evaluated with the following wound types:

| Traumatic wound x2 | Category 2 pressure ulcer x4 |

| Leg ulcer x3 | Superficial dermal burn |

Patient progress was monitored and photos and assessments were taken at each dressing change to illustrate how the wounds had progressed using the ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid.

The ten patients comprised of six males and four females, the exudate levels of the wounds were assessed between low to medium levels of exudate. On average the dressings were changed between 5 and 7 days. In all ten cases the ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid was used as a primary dressing. The data was analysed and is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Data from the ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid assessment

The evaluation of the data showed that in the case of ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid’s ability to manage exudate, 41% of the responses were very satisfied and 59% were satisfied.

In maintaining a moist environment 41% were very satisfied and 59% satisfied. In regards to ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid’s conformability, 35% were very satisfied and 65% satisfied. The product was also assessed for ease of use, 41% were very satisfied and 59% were satisfied. It was also documented on the assessment forms that ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid was easy to apply and did not cause any underlying trauma to either the surrounding skin of the wound or through maceration to the peri-wound area. It was also documented that seven out of the ten wounds healed using the ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid.

The nurses reported that the dressings were able to effectively remove devitalised tissue of both necrosis and slough. The nurses also reported that it was effective in the management of the wound and remained in place for the recommended wear time. The patients also reported that the dressing was very comfortable as they had forgotten that the dressing was on their wound.

Overall 41% of the respondents were very satisfied and 59% satisfied with the product, this suggests that patients with wounds that have been assessed to remove devitalised tissue with low to medium exudate levels will have a positive experience when ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid is used. In all of the wounds assessed and evaluated there was progress through the wound healing continuum, this resulted in the removal of devitalised tissue and the promotion of wound healing.

CASE STUDY

Mrs C was an 83-year-old female. She attended the wound care clinic having dropped a hot cup of tea onto the upper thigh of her left leg (Figure 11).

INITIAL PRESENTATION

At the initial examination the wound presented with both granulating and epithelial tissue, however, there was a 10% area of slough. The patient’s wound was fully assessed and a superficial dermal burn was identified.

The priority for this wound was to debride the devitalised tissue through the facilitation of autolytic debridement. ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid was chosen to assist in the rehydration of the wound, to remove the devitalised tissue and facilitate autolysis. The ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid contains a blend of synthetic polymers and hydrophilic powders which provide a self-adhesive absorbent material for wound applications. As well as providing a bacterial barrier to the wound site, the wound dressing also absorbs exudate to form a cohesive gel that promotes a moist wound healing environment. Benbow (2005) states that hydrocolloid dressings are indicated for wounds with low to medium exudate, from which they can absorb and hold exudate in the hydrocolloid matrix. They are completely impermeable to water and therefore support rehydration and autolytic debridement of necrotic and sloughy wounds.

The product was also chosen to provide a moist environment and promote both granulation and epithelisation. The ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid would provide a bacterial barrier to prevent infection and contamination but also enabled the patient to wash and shower as the dressing was waterproof.

The dressing was changed a week later (Figure 12). The wound had started to debride autolytically with the application of the ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid. The sloughy tissue has started to lift and there was an increase of granulation tissue and epithelial tissue visable at the wound edges. The same dressing regime was continued.

By week four (Figure 13) the wound had completely healed and the dressing was discontinued and Mrs C was discharged. Throughout the treatment of the superficial dermal burn the dressing was easy to apply and was conformable. The dressing stayed in place and was easy to remove without causing any trauma to the wound and surrounding skin.

DISCUSSION

The performance of ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid demonstrated by the results and the case study are encouraging. The evaluation suggests that the ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid is an effective wound care choice that has shown effective removal of devitalised tissue and created the right environment for healing and wound progression. All the patients within the study showed signs of healing and wound progression; 41% were very satisfied and 59% were satisfied with the overall performance of the dressing.

The outcome of the evaluation study demonstrated that ActivHeal® Hydrocolloid possesses the required attributes of a hydrocolloid dressing for usage on a range of both acute and chronic wounds.

ACTIVHEAL® HYDROGEL RESULTSVisit product page

Carolynne Sinclair, Tissue Viability Nurse, Countess of Chester NHS Foundation Trust, Chester

The results gained from the dressing assessment of the ActivHeal® Hydrogel dressing range were collated and analysed.

Eleven patients’ wounds were evaluated with the following wound types:

| Necrotic pressure ulcers x6 | Devitalised tissue following forefoot amputation | Dehisced abdomen with dry necrosis |

| Pressure ulcer left hip category 3 | Grade 4 pressure ulcer sacrum x2 |

Patient progress was monitored and photos and assessments were taken at each dressing change to illustrate how the wounds had progressed using ActivHeal® Hydrogel.

The 11 patients comprised of six males and five females, the exudate levels of the wounds were assessed between dry to low levels of exudate. On average the dressings were changed either every day or on alternate days. In all 11 cases the ActivHeal® Hydrogel was used as a primary dressings and ActivHeal® Foam dressing was used as a secondary dressing. The data was analysed and is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Data from the ActivHeal® Hydrogel assessment

In maintaining a moist environment 71% were very satisfied, 25% satisfied and only 4% dissatisfied. In regards to ActivHeal® Hydrogel’s conformability, 75% were very satisfied and 25% satisfied. All respondents were very satisfied with the product’s ease of use. It was also documented on the assessment forms that ActivHeal® Hydrogel had a high viscosity, was easy to apply and did not cause any underlying trauma to either the surrounding skin of the wound or through maceration to the peri-wound area.

Anecdotally, the nurses also reported that the dressings were able to effectively rehydrate and remove devitalised tissue of both necrosis and slough and that on three occasions only one application of the ActivHeal® Hydrogel was necessary. The nurses also reported that there was minimal residue left on the wound prior to reapplication of the gel, suggesting that the absorption of the product had occurred and a degree of rehydration had been achieved.

An overall rating of 79% of the respondents were very satisfied and 21% satisfied with the product, which supports that the product is acceptable for wounds that have been assessed to remove devitalised tissue with dry to low exudate levels. All of the wounds assessed and evaluated progressed through the healing continuum, with devitalised tissue being removed.

CASE STUDY

Mrs B was a 94-year-old female with a past medical history of diabetes and hypotension. The patient was admitted following a fall with reduced mobility and was generally unwell. On admission the patient was fully assessed and an area on her right buttock was discoloured with areas of necrosis (Figure 15) and the patient was referred to the tissue viability team.

INITIAL PRESENTATION

At the initial examination the wound presented as an area of necrosis with little exudate. The cause of the wound was pressure and moisture as the patient was incontinent of both faeces and urine. The patient was also non-concordant and refused to be turned or tilted. However, she did agree to be nursed on a pressure-relieving mattress.

It was difficult to assess the depth of the tissue involvement in this lesion as necrotic eschar was present and therefore it was decided debridement was required to facilitate a diagnosis of depth. The European Pressue Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) classification system has attempted to address the difficulty of categorising a necrotic lesion by using an unclassified/unstageable classification. This descriptive definition discusses it as full thickness tissue loss in which the actual depth of the ulcer is completely obscured by slough and/or eschar in the wound bed. Until enough slough/eschar is removed to expose the base of the wound, the true depth cannot be determined (EPUAP, 2009).

The priority for this wound was debridement, this was achieved using a rehydration method that facilitated autolytic debridement. ActivHeal® Hydrogel was chosen to assist in the rehydration of the wound, to remove the devitalised tissue and facilitate autolysis. The ActivHeal® Hydrogel contains 85% water and a collection of polymer chains that are water insoluble and is indicated for the management of necrotic and sloughy wounds with nil to low exudate including pressure ulcers, cavity wounds, leg ulcers, skin donor sites and diabetic foot ulcers. Hydrogels donate moisture to provide a moist environment, this encourages and facilitates autolysis or debridement of devitalised tissue from the wound bed (Morris, 2006).

The secondary dressing that was used was ActivHeal® Adhesive Foam which was chosen to ensure the hydrogel remained in place, while maintaining a moist wound environment. The ActivHeal® Adhesive Foam also provided a bacterial barrier to prevent infection and contamination but also enabled the patient to wash and shower as the dressing is waterproof.

Dressing changes took place daily. The wound continued to debride autolytically with the application of the ActivHeal® Hydrogel and ActivHeal® Adhesive Foam dressings. The necrotic tissue started to soften and there were small areas of granulation visible at the wound edges. The same dressing regime was continued for the duration of week 2 (Figure 16) and by the end of the week further debridement and removal of devitalised tissue was evident (Figure 17).

By the third week of treatment the wound had been fully debrided of devitalised tissue (Figure 18). The wound was producing higher levels of exudate, it was reassessed and the treatment regime changed to ActivHeal Aquafiber® and ActivHeal® Foam Adhesive. This was to ensure that the wound continued through the wound healing continuum and to prevent any maceration to the peri-wound area.

DISCUSSION

The performance of ActivHeal® Hydrogel demonstrated by the results and the case study are encouraging. The evaluation showed that ActivHeal® Hydrogel is an effective wound care choice that has shown successful removal of devitalised tissue and has created the right environment for healing and wound progression. This is demonstrated by the fact that all of the patients within the study showed signs of healing and wound progression. Seventy-nine percent of respondents were very satisfied and 21% were satisfied with the overall performance of the product.

The outcome of the study supports the usage of ActivHeal® Hydrogel and demonstrated that the product has the required attributes of a Hydrogel dressing for use on a range of chronic wounds.

CONCLUSION

The Department of Health’s Quality Agenda including QIPP (Quality, Innovation, Prevention, Productivity) identified and highlighted the importance of all health professionals working towards maintaining and developing patient safety, patient experience and clinical effectiveness.

Approximately 3% of the NHS budget is spent on treating chronic wounds, costing the NHS £2–3 billion per annum, based on an estimate of 200 000 people in the UK suffering with a chronic wound (Posnett and Franks, 2007). As the ageing population continues to increase, the amount of chronic wounds will inevitably increase, as will the cost to the NHS of treating these wounds. Interestingly, Vowden et al (2009) undertook a local audit exploring the incidence of wounds and suggested that approximately 3.55 per 1000 of the population had a wound of some kind. It is therefore vital that practitioners in both primary and secondary care are able to access products that meet the needs of their patient’s wounds and are cost effective.

This clinical supplement has presented and evaluated the successful use of ActivHeal® dressings on a pressure ulcer, leg ulcer, dog bite and burn. All patients involved in the evaluations were over 18 years of age and the clinicians evaluating the effect of the products on the wound healing continuum were all tissue viability nurses.

Visual representation of the results are presented in Graphs 1-5.

10 patients were recruited for the evaluation of the ActivHeal

Aquafiber® dressing

11 patients were recruited for the evaluation of the ActivHeal®

Foam dressing range

10 patients were recruited for the evaluation of the ActivHeal®

Hydrocolloid

Despite experiencing increasing demand for care and services, in the context of a diminishing income and economic crisis, the NHS has been asked to find £15-20 billion of savings over 4 years (Foster and Bolger, 2010) which is to be reinvested so that the burgeoning care deficit can be addressed. Nurses are well placed to be innovative by examining process and cutting out duplication and waste. It is imperative that we benchmark practices that align to the ideals of a quality, cost-effective and productive service which focuses on safety, effectiveness and patient experience. In relation to the quality agenda there is a need to ensure that wound care products are able to assist the health professional in the management of wounds. Every dressing change will have an impact on the patient experience; therefore, evidence outlining the effectiveness of wound care products can support health professionals in their roles to select quality products that assist in wound management.

The case study evaluations present excellent patient outcomes, demonstrating the ActivHeal® wound care products’ ability to manage exudate; maintain a moist wound environment; conformability to the wound and ease of use for practitioners.

Choosing the correct and appropriate dressing to manage a wound is essential, with practitioners ensuring that their choice of product is based on the best available evidence while ensuring cost effectiveness. This supplement has presented case study and assessment evidence which supports the ActivHeal® range in providing practitioners with products that manage the complexities of promoting moist wound healing in a cost-effective manner.

Beldon P (2010) How to choose the appropriate dressing for each wound type. Wound Essentials 5:140-4

Benbow M (2005) Evidence-based wound management. Whurr Publishers Ltd., London

Collier M (2002) Wound bed preparation. Nurs Times 98(2): 55-7

Department of Health (2009a) Prime Minister’s Commission on the Future of Nursing and Midwifery. DH, London. http://tinyurl.com/35qvc6y (Accessed 13 July 2011)

Department of Health (2009b) NHS 2010–2015: From Good to Great. Preventative, People-Centred, Productive. DH, London. http://tinyurl.com/yc2nbe3 (Accessed 13 July 2011)

Department of Health (2010a) Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS. DH, London. http://tinyurl.com/5w96kr6 (Accessed 13 July 2011)

Department of Health (2010b) Pressure ulcer productivity calculator. DH, London. http://tinyurl.com/355cta4 (Accessed 13 July 2011)

European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (2009) Prevention and Treatment of pressure ulcers: quick reference guide. NPUAP, Washington DC

Foster D, Bolger G (2010) The Quality and productivity challenge. Wounds UK 6(4): 203-6

Gray D, Cooper P, Timmons J (2006) Essential Wound Management: Introduction for undergraduates. Wounds UK, Aberdeen

Hawkins E (2010) Using ActivHeal® in a traffic light system wound care formulary. Wounds UK 6(4): 177-82

Horkan L, Stansfield G, Miller M (2009) An analysis of systematic reviews undertaken on standard advanced wound dressings in the last 10 years. J Wound Care 18(7): 298-304

Lewis S (2009) Using ActivHeal dressings in a London teaching hospital: a cost analysis. Br J Nurs 18(20)Suppl: 38-42

McKenna DJ et al (2007) Nicorandil-induced leg ulceration. Br J Dermatol 156(2): 394-6

Morris C (2006), Wound Management and dressing selection. Wound Essentials 1: 178-83 Nelson EA, Bradley MD (2007) Cochrane Database Syst Rev Jan 24;(1): CD001836. Dressings and topical agents for arterial leg ulcers. University of Leeds, School of Healthcare, Baines Wing, Leeds. http://tinyurl.com/6yj7k5f (Accessed 15 July 2011)

Posnett J, Franks PJ (2007) ‘The cost of skin breakdown and ulceration in the UK’. In: Skin Breakdown the Silent Epidemic. Smith and Nephew Foundation, Hull

Posnett J, Franks PJ (2008) The burden of chronic wounds in the UK. Nurs Times 104(3): 44–5

Thomas S (2000) Alginate dressings in surgery and wound management – Part 1. J Wound Care 9(2):56-60

Touche R (1993) The Cost of Pressure Sores. Report to the Department of Health. DH, London. http://tinyurl.com/2w8deuh (Accessed 22 July 2011)

Winter GD (1962) Formation of the scab and the rate of epithelisation of superficial wounds in the skin of the domestic pig. Nature. 193: 293-4

Vowden K, Vowden P, Posnett J (2009) The resource cost of wound care in Bradford and Airdale primary care trust in the UK. J Wound Care 18(3): 93-102

CONTACT US FOR MORE INFORMATION

* Required Field

ActivHeal® is a trademark of Advanced Medical Solutions.

Discover ActivHeal®

Social Media

Our Product Range

AMS Group

ActivHeal®, its logo and the Advanced Medical Solutions logos are registered trademarks of Advanced Medical Solutions Ltd.

Copyright © Advanced Medical Solutions Limited | Design by Lumisi Ltd